The Visibility of Machine Translation

Machine translation has been studied for a long time, increasing in prominence following World War II and, though there was a decline in funding after it failed to reach perfection, never really falling out of favor since then [2]. Despite this progress, more translators are being hired than ever [3]. While machine translation is used frequently among individuals or in certain corporate settings, it is not used nearly as often in the legal, public, and artistic spheres, where human translators are the status quo. Why is that? While for the legal and public spheres, it is almost entirely because of the likelihood of error that machine translation goes unused (and as that likelihood of error decreases, its use in the public sphere slowly increases [4]), among authors it is more complicated than just that. Translation can be considered an art in itself, though one that often aims to be “invisible” [5]. The goal of a translator, in general, is to produce the same effect of a source in a different language. With things that are pure information like textbooks or manuals, this is relatively simple, but what of poetry, where the form of words is just as important as what meaning they carry? While many artists find the works of machines interesting, more still hold that art is something beyond what machines can produce. I’m not sure what I think about that, but machine translation, even when entirely correct, has a certain stiltedness to it that makes it unsuited for things like music, poetry, and even literature.

Machine translation as a practice has its roots in the Cold War. While machine translation had been considered theoretically beforehand, the first forays considered successful took place in the mid to late 1950’s [6], between English and Russian – with American scientists developing Russian-to-English translation, and Russian scientists developing English-to-Russian translation. However, the goal of “Fully Automated High-Quality Machine Translation” was realized to be infeasible – language is simply too ambiguous. Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, who was once a proponent of machine translation, succinctly described this with these constructed sentences: “The pen is in the box” and “The box is in the pen” [2]. Which meaning of pen is meant affects what it will be translated as – but computers can’t easily tell which they should use. These early machines were used mostly for scientific papers, where there is little ambiguity and lots of technical terms, well suited for machine translation, but when ambiguity arises, machines do worse.

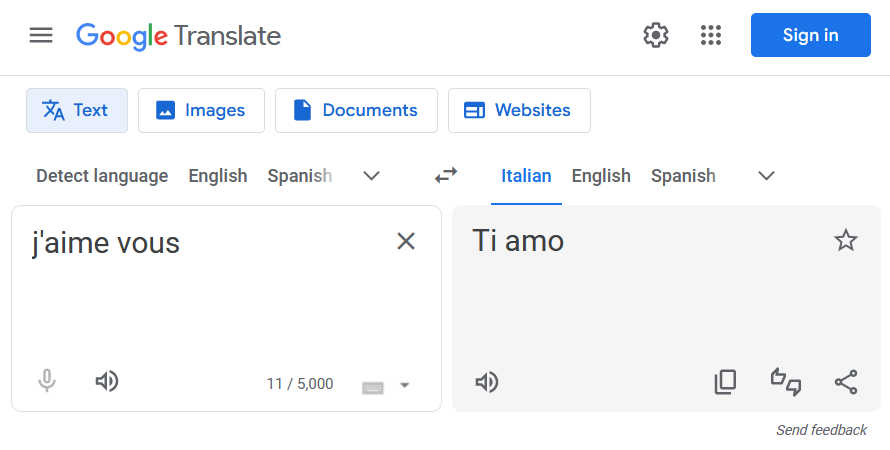

Machine translation as it is now is very good between some languages, but not nearly as good between others. Generally, the more closely related languages are, the easier it is to translate between them. While this holds true for machine translation, most machine translation tools available between multiple languages online, including the most-used machine translation tool, Google Translate [7], do not translate directly between most languages. Instead, English is used as a go-between in most cases, even when the languages are closer to each other than to English. See Figure for a clear example in French and Italian [8]. Some languages do not have a direct translation to English either, instead being translated first to a closely related language. This leads to a possible daisy-chain of translations, say, from Ukranian to Russian to English to Czech and finally to Slovak, despite the two endpoints, Ukranian and Slovak, both being Slavic languages.

The most common use of machine translators is personal use, to learn or to communicate with another person with whom one does not share a language. Machine translation is generally good in both cases. While machine translation can be stilted, it generally gets the gist across – most of what is needed when, for example, asking someone if this is their wallet one found on the ground, or even reading a basic encyclopedia article. Machine translation should not be used when there is significant risk if communication fails [7]. In larger conversations, especially those with people of varying skills of various languages, machine translation can be used, but should be used minimally [9]. Machine translation is also used when learning a language [7] [10] – I know that most of what I use machine translation for is English to French, or French to English, despite being technically fluent in both languages. It should not, however, be used as a replacement for a good bilingual dictionary, as machine translation is heavily context dependent. While some synonyms or alternate translations may be listed, a dictionary, especially one with things like etymologies and conjugations, will be significantly more helpful for language learning.

Instead of being mostly rule-based like those early machine translators, more modern machines have turned to artificial intelligence. While this has improved translation overall, it has only decreased machine translation’s ability as a dictionary. Translation has always held some sway over artificial intelligence, with John Searle’s “Chinese Room” scenario, a very well-known thought experiment, drawing an especially tight comparison [11]. Despite the many and varied ways that the thought experiment has been contested, it is even now, forty years later, often brought up when talking about artificial intelligence, especially with regards to translation. The scenario is thus: Searle himself (who does not speak Chinese) is in a room with a computer that asks him questions in Chinese. Using the vast amounts of information (in Chinese) and rules (which are about Chinese, but which he can understand) available to him in the room, he is able to put together answers to the computer’s prompts. The question is thus: Can Searle be said to understand Chinese? And, because he self-professed he cannot, can any computer program (which he is playing the role of in this scenario) be said to understand Chinese? Searle thinks not, and has many rebuttals to arguments for machine understanding. I think whether a machine understands a language or not is irrelevant – what matters is intentionality, which machines are programmed with. However, the kind of intentionality necessary for literary or poetic translation work is lacked by machine translators – machine translation is only ever sense-for-sense, if not literal.

When translating poetry or literature, the form of the language can be just as important as the meaning of it – more, in some cases. Some translated works, especially those from especially old sources or those translated from languages far removed from English, are prefaced by or peppered with translator’s notes. These notes help put in context what decisions the translator has made or highlight a structure of the language that English simply lacks. Notes about translation decisions are not something that machine translation can generate, because it does not make decisions in the same way a human translator would; If a human translator chooses to leave a word untranslated, there could be any number of reasons why, while if a machine translator leaves a word untranslated, it doesn’t know the translation of the word. Even for works without translator’s notes, different languages have different stylistic preferences that can be felt if you know where to look. French, for example, has many small connecting words, while English is very dense. Translating between the two will inherently affect the structure of the work.

Even when the translator is the same as the original author, as with Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot (originally French En attendant Godot), there will be differences. The differences between the two scripts of Godot are interesting – an increase in eye-dialect and changes to stage instructions the most memorable to me [12]. Beckett also used the translation as a last chance to edit the play. Content editing is not uncommon in translation, and while some find it problematic, I find it inevitable. If a translator has the power to reduce a sexist rant from several pages down to one [2], well, why not?

In his introductory translator’s note to the very well-known Japanese novel Botchan, Yasotaro Morri states that “No translation can expect to equal, much less to excel, the original” [13]. While I would not say that this is a hard rule, there is certainly truth to it, but sadly no one person can learn every language. Translation not only allows those who don’t speak the original language to experience a work in some form, it also creates a new work. One of my favorite parts of reading old and frequently translated works like Beowulf, Dante’s Inferno, or what remains of Sappho’s poems is that plurality of perspectives. Through multiple translations, an interested reader can triangulate the meaning and the feeling of the original.

To conclude, a passage from the opening of Corinne Atlan’s Le pont flottant des rêves, in the original French [14], as well as two English translations – one machine translated [8], the other translated by me.

J'ai aussi pressenti, d'emblée, que le traducteur ne pouvait être ce personnage invisible à qui l'on demande de « s'effacer » totalement derrière le texte original. Il ne s'agit pas seulement d'une opération technique. Avoir le goût de la littérature et connaître le mieux possible les ressources des deux langues en jeu sont des conditions nécessaires mais loin d'être suffisantes. La traduction littéraire est une activité de création, davantage liée à la question de la représentation artistique du réel qu'à un savoir académique. Traduire ne fait pas seulment appel à l'intellect, mais à une intelligence des choses poétique, sensible. Comme tout processus d'écriture, cela engage l'ensemble de l'être : émotions, perceptions, imagination, souvenirs de lecture ou de vie, les deux d'ailleurs souvent mêles. Sans compter le rôle que joue dans toute authentique rencontre, humaine comme littéraire, le réseau de racines souterraines qui court au fond de chacun de nous et nous relie à notre insu les uns aux autres.

Original French

I also sensed, from the outset, that the translator could not be this invisible character who is asked to “efface himself” completely behind the original text. It is not just a technical operation. Having a taste for literature and knowing as much as possible the resources of the two languages involved are necessary conditions but far from being sufficient. Literary translation is a creative activity, more linked to the question of the artistic representation of reality than to academic knowledge. Translating does not only call on the intellect, but on a poetic, sensitive understanding of things. Like any writing process, it involves the whole being: emotions, perceptions, imagination, memories of reading or life, the two are often mixed. Not to mention the role that plays in every authentic encounter, human as well as literary, the network of underground roots which runs deep within each of us and unknowingly connects us to each other.

Google Translate

I have also found that a translator can't just be an invisible character who is demanded to totally erase themself from the original text. They don't act solely on technical operations. To have taste for literature and know of the best possible resources between both in play are necessary conditions but are not, by themselves, sufficient. Literary translation is an act of creation, more bound to the question of what to value between artistic and academic truth. Translation is not only a call for intelligence, but a call for a sensitive, poetic intelligence. Like all writing processes, it involves the whole of being: emotions, perceptions, imagination, memories from readings or from life, those last often blended together. Without mention the role played in each authentic encounter, human or literary, of that web of roots that deeply connect the essence of each of us, with or without our knowing.

My translation

References

- M. Oldman and A. Dahāka, "Retrofuturological Linguistics, Part I—The Future of Linguistics as Seen from the Past," Speculative Grammarian, vol. CXCIII, no. 3, January 2024. [Online]. Available: https://specgram.com/CXCIII.3/10.oldman.retrofuturological1.html. [Accessed 24 April 2024]

- D. Hofstadter, Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language, New York City: Basic Books, 1997.

- Y. Balashov, "The Translator's Extended Mind," Minds & Machines, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 349-383, Sep2020.

- J. Edlinger, "Translation AI Helps Bridge Language Barrier for Minnesota DVS," Government Technology, 28 September 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.govtech.com/artificial-intelligence/translation-ai-helps-bridge-language-barrier-for-minnesota-dvs. [Accessed 27 April 2024].

- A. Carson, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, New York: Vintage Books, a division of Random House, 2003.

- M. J. Nye, "Speaking in Tongues," Distillations Magazine, [Online], 29 June 2016. Available: https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/speaking-in-tongues. [Accessed 27 April 2024].

- L. N. Vieira, C. O'Sullivan, X. Zhang and M. O'Hagan, "Machine translation in society: insights from UK users," Language Resources & Evaluation, vol. 57, no. 2, pp. 893-914, Jun2023.

- Google, "Google Translate," [Online]. Available: https://translate.google.com. [Accessed 24 April 2024].

- M. Pituzcoosuvarn and T. Ishida, "Multilingual Communication via Best-Balanced Machine Translation," New Generation Computing, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 349-364, Oct2018.

- Á. M. López González and L. V. Pinzón Alarcón, "Breaking Barriers: Exploring the Role of Google Translate in Empowering Productive Skills in Language Learning," Revista Panorama, vol. 17, no. 33, pp. 67-80, jul-dic2023.

- J. R. Searle, "Minds, brains, and programs," The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 417-424, 1980.

- S. Beckett, Waiting for Godot - Bilingual Edition, New York City: Grove Press, 2010.

- Y. Morri, "Translator's Note," in S. Natsume, Botchan, Tokyo, Ogawa Seibundo, 1918, pp. i-viii.

- C. Atlan, Le pont flottant des rêves, Lille: La contre allée, 2022.

Originally written for Engineering Ethics and Safety Spring 2024, my favorite class that semester. Thanks Daniel! Sorry I almost failed the other class I took from you!